After the last student council elections in November 1993 and before the scheduled elections in November 1994, students at Birzeit decided that they wanted to change the system of election to, and structure of, the student council.

For 20 years, student politics at the university had been dominated by a first-past-the-post system that led groups to a prevailing "all or nothing" belief, affecting everything from the style of their campaigns to the resulting pre-election coalition deals stuck by the most unlikely minority parties in attempts to secure representation for their points of view.

This status quo, the growing worldwide popularity of proportional representation electoral systems, and certainly the influence on students of seeing the processes of the Israeli proportional representation system reported in the media, have combined to prompt this change, which the majority of students feel is for the better.

In a referendum in the weeks prior to the election in which 49 percent of eligible students voted, 74 percent opted for the new system. Director of Student Affairs Nazmi Ju'beh, also Head of the Elections Committee, explained that this vote was confirmed by another referendum that took place on the day of the election, "2,384 students voted on the new system, 2,005 expressing support for it and 336 against it. There were 43 spoilt papers. This means that 85.6 percent of those who voted were in support of the new system, or 71.6 percent of the whole student body. An overwhelming majority."

Preparations for the system took a long time. Details were thrashed out by the different student blocs, resulting in a very structured set of guidelines for candidates, the campaigning process and the formation of the student council.

"The students did a great job," says Ju'beh, who coordinated the restructuring. A Birzeit graduate himself, who worked first as a history lecturer before being appointed to head the Office of Student Affairs, Ju'beh has both the perspective of the students and his experience in the university to draw from. The students, who recognise that they are dealing with someone with an understanding of their priorities, have appreciated his assistance and understand that there is no favouritism. This proved important as, "there was a dominating mentality that the bigger the party, the more rights it has," according to Ju'beh, "This year everyone has had to respect the existence of other blocs."

Independent candidates who chose not to stand for election on the traditional Palestinian party-political lines ran for the first time this year, and although none gained a seat, this was a significant development.

Students now elect a 51-seat parliament that is to decide all important student issues. Blocs of students representing different ideologies and approaches to the student council are registered 3 months before the election with the overseeing committee, and are submitted by blocs representing different parties. The percentage of votes from the election are calculated to decide how many seats each bloc gets.

After the election, the factions decide which of their candidates will be chosen for their available seats. From this base, a majority vote by the members decides a further, more focused governing body or "cabinet" of 11 members including the student council president.

The proposal for the composition of the cabinet is initially made by the party with the largest number of seats in the student parliament. This is expected to be the time when groups try to form coalitions to secure the best deal for themselves. Nazmi Ju'beh smiles as he said, "Each party gets a week to try. If the largest party doesn't succeed in forming a cabinet, the next largest party gets to try, and so on. If everyone fails then I, as Head of the Elections Committee, will choose a directly proportional cabinet. With 51 seats in the parliament, a party will get one representative in the cabinet for every 4.6 seats they hold."

In the last elections, during November 1993, in what was satirically described by some as an "unholy alliance", left-wing parties joined in a pre-election coalition with the Islamic bloc to coax power from the pro-Arafat Shabiba faction that had dominated student politics for eight years. In the wake of the "Gaza-Jericho First" Oslo accords, the coalition ran on a "Jerusalem First" ticket, gaining control of the student council by 120 votes under the previous "winner takes all" system.

Ellen Saba, a representative of the left-wing Labour Front who was elected to the 1993/94 student council, commented at the time that, "I don't find it strange that a Christian woman like myself runs for the same list as the Islamic Bloc; it is a matter of winning or losing."

Naturally, the left-Islamic marriage led to a compromise on both sides in how the coalition presented itself during the election campaign. The new regulations prevent this from happening. Nazmi Ju'beh commented that, "Because pre-election coalitions were forbidden, the blocs' identities were clearer this year and now we know exactly the influence of each bloc."

In the week prior to the elections, the time permitted for campaigning was reduced from three-and-a-half days to just two. "This meant that it was less expensive for the various student blocs this time," says Ju'beh, "and as everyone knew they were likely to get represented under the new system, campaigns were not so excessive."

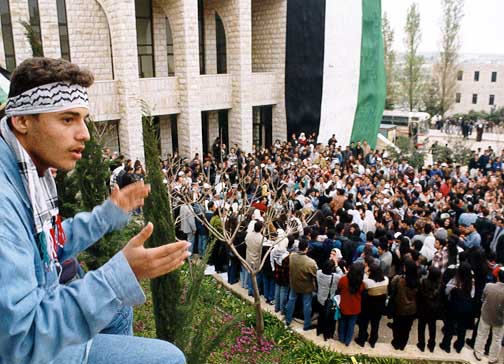

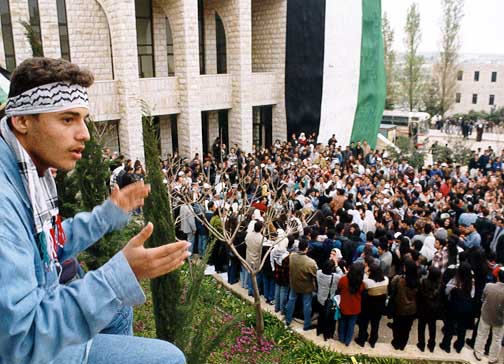

Locations for big banners and time-slots for the rallies of the different blocs were allocated by the time-honoured method of pulling pieces of paper out of hats. The elections went smoothly, "without any critical moments", with even right-wing Israeli daily The Jerusalem Post reporting on May 31st that they "passed without fuss or incident". Ju'beh put this down to the new system, "Everyone was sure to be represented." In fact the result," in Ju'beh's opinion, "was pretty much the same as last year. Nothing much changed."

Birzeit Public Relations Director Albert Aghazarian cited that the 1995 elections at Birzeit were, "a model for Palestinian democracy." The university has a history of encouraging the democratic process. Vice-President Ibrahim Abu Lughod headed a committee established in the wake of the Oslo accords to make recommendations to the Palestinian Authority about the system that should be employed for the impending national elections.

The elections this year were attended by representatives from the Nablus-based Centre for Palestine Research and Studies, who were interested to observe the voting and counting process.

Last elections, two months after the September 1993 Oslo accords, were an opportunity for students to voice their opinions about the nature of the peace agreements. As Palestinians have no elected national representatives under occupation, student elections are seen as a barometer of Palestinian public opinion. Professor Riad Malki, from Birzeit's engineering department, commented at the time, "The elections are important because they are political and reflect the mood of the people after the signing of the autonomy deal."

Consequently, most of the political groups include national issues in their campaigns. "At the time of the Oslo accords," Ju'beh pointed out, "Palestinian society was polarised into two camps - those who supported that particular peace deal and those who didn't. This year there was less emphasis on national issues, reflecting the changing mood of the people. A year and a half after the deal those "pro" it are less pro and those "anti", less anti."

"We saw an increased focus on student issues, including: the comprehensive exam students have to take at the end of their degree course; the cost of student tuition fees; the prices in university cafeterias; the participation of masters students in the life of the student council; and the role of independents in student political life."

Many of the groups did make symbolic and political references to the ongoing issues of the peace process; one bloc calitself the "Al-Quds (Jerusalem) Bloc", the "Progress and Democracy Bloc", and another, the "Homeland and Democracy Bloc".

Students also held a debate, and in their rally presentations included sketches, music, and dancing; the atmosphere often more reminiscient of a party than an election. Julia Hawkins, an international student studying Arabic at Birzeit, commented, "It was a long way from the lethargy of the kind of student union elections I am used to in Britain."

The new election regulations currently do not consider a student who is studying for a diploma or a masters degree programme eligible to vote. The students decided this as they felt that these students, who are generally mature students and part-time, do not participate in university life enough to make informed decisions affecting the welfare of all students.

At the moment, with their negligible numbers, this perhaps is not a huge issue, but Nazmi Ju'beh estimates that in the next two or three years, as the masters programmes expand, there will be 300-400 students to contend with. "Then", he says with a twinkle, "There may be a problem!"

Whatever the processes that elections are due to go through in the next few years, what is clear is that students, faculty and administration are getting a profound insight into the development and, indeed, excitement of the road to democracy.

This article first appeared in Birzeit Newsletter No.26