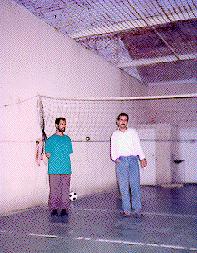

Left: Zaher Subbah (left) and Mustapha Atari stand in the volleyball court in one of the open areas in the prison, where the sky is only visible through bars.

In the period after the hunger strike, the Ramallah prisoners saw a marked relaxation of restrictions. Cell doors were no longer locked inside the prison complex. Occasionally, some prisoners are given day release, to visit their families or write an exam.

Still, the situation is heartbreaking and the more I visit the students, the worse it gets. What do you say to people imprisoned for no good reason? What does it say to them about the 'Authority' responsible for putting them in prison? What do you say to a PA First Lieutenant who grills you a couple of times when you start visiting, trying to find out why you care about the students as a foreigner? What do you feel like saying to him?

In one conversation with the Subbah brothers, I suggested that their pattern of detention without charge or trial was similar to Israel's use of administrative detention. "No! It's worse!" said Fakhri, "In this case, we haven't been told the period we are going to be in detention."

Consequently, detention is far more unstructured than it would have been in Israeli jails, where prisoners held educational lectures and other activities. Here they waste away, frustrated, under an weighty timelessness that reminds me of Samuel Beckett's Waiting for Godot, a rather play I read at school that many people mention to be hip. Prison isn't funny? You'd be surprised.

Right: Fakhri Subbah and his father, standing in one of the two 8x16 meter open areas on a visiting day.

During my third of over fifteen visits, when hopes of a release during the `Eid al-Adha (lit. "Feast of Sacrifice", Muslim equivalent to the Jewish Passover holiday) had died down in the wake of the holiday, I asked them what they had done when they had realised they were not going to be freed.

"We slept a lot," said Bassim, "we were very sad. Maybe after the Israeli elections."

His brothers nodded agreement.

Sitting nearby and grinning cheekily, Birzeit architecture student Ammar Al-Wahidi, recently transferred from the prison in Jericho, quipped "The Israeli elections are a new Palestinian national holiday!"

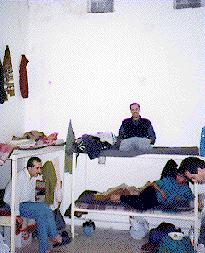

In the Subbah brothers' cell (left) in the Muqata'a, all eight prisoners are students or graduates of Birzeit and Bethlehem universities.

This stands in stark contrast to the education of those in charge of jailing them. According to those recently transferred from the Jericho Mukhabarat (Intelligence) detention facility, its head, a senior PA figure with a branch office in Ramallah, is reportedly unable to read or write. Many of the prison guards are in the same situation.

The guard allocated the responsibility for collecting prescriptions for the Jericho prisoners used to empty the sack of medicines onto the floor and call people to come and collect their own because he couldn't read. The prisoners - most of them university students - developed a routine each time he came where one would innocently announce in a loud voice to his fellow prisoners as the sack was poured out, "Guys. If any of you have difficulties reading or writing, try to recognise your medicine bottle by its colour and shape."